Most people who drive – or even walk – past borough hall in Seaside Park would be forgiven if they didn’t notice the history just feet away from them, or how it may have vanished if not having been preserved so well. Ironically, during its heyday, what is now “borough hall” was located in a town that didn’t yet exist – it was Toms River’s waters this place was meant to protect, even after the closure of Cranberry Inlet.

Though borough council meetings are held in the meeting room above the police station a bit further south, the daily business of the now-independent Seaside Park (which celebrates its 125th anniversary this year) is conducted at the weathered, New England coastal-style building located at the corner of North Ocean and Decatur avenues. A closer look, inside and out, shows how that history was made, and how lives were saved when it was built as part of a network of similar structures up and down the barrier island by the United States Life Saving Service, the precursor agency to today’s U.S. Coast Guard.

What was known as “Toms River Life Saving Station No. 13” was built in 1872, and even after powerboats replaced the crew-portable surf boats decades later, the station remained active until 1964 using amphibious vehicles designed for use in World War II. By then, the modern Coast Guard was utilizing stations primarily situated near inlets on the bayside where heavy-duty fast boats could be launched, eliminating the need for the old Life Saving Service stations with their lookout towers and massive bay doors. Seaside Park’s station, in many ways, is unique because of the length of time it was in service and the fact that it almost met a particularly unceremonious demise.

“I can’t believe it could’ve been a McDonald’s,” said Borough Councilman Ray Amabile, 78, with a chuckle.

Amabile himself is a U.S. Coast Guard veteran who was trained in search-and-rescue missions and served in numerous locations, including locally at Station Shark River in Monmouth County. After the Coast Guard closed the old Seaside Park station in 1964, its ownership was transferred to the borough two years later, but activity ceased soon thereafter. When fast food chains were growing rapidly across American as the postwar “baby boom” expanded domestic travel, an idea to build a McDonald’s restaurant along the ocean was thought up by a local franchisee – and the then-derelict building seemed like a good spot off the boardwalk.

Amabile credits John Peterson, the borough’s current mayor, for leading the charge to restore the Life Saving Station and turn it into something useful – in this case, town hall itself following a renovation in 1996. But while it isn’t necessarily unusual for government offices to be located in historic buildings, Seaside Park’s former Life Saving Station holds a fascinating number of unique but otherwise unremarkable features that provide a great deal of insight into how these early Life Saving Stations operated, and how the men who crewed them saved lives.

Big Doors, Small Boats

Those who come to the building to take care of routine business at town hall enter from the side, but the front of the building is where one of its most important features is located.

The “bay doors,” which resemble two immense, white barn doors, now house office space – but were once opened in emergencies to allow crews to physically carry surf boats from the building to the ocean. Upon spotting a ship in distress, crews would rush to hoist the boats to the beach, launch them into the ocean (day or night) and use the rudimentary life-saving equipment of the time to bring mariners safely to shore.

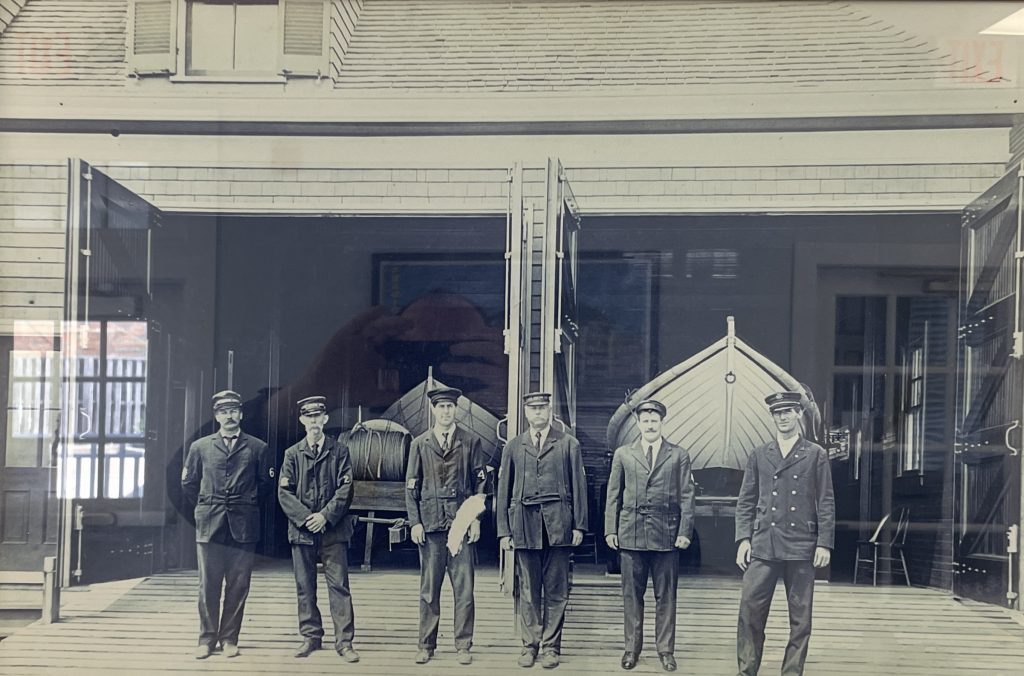

“Four hours on, eight off, and they just went back and forth, constantly,” Amabile said, of the crews’ schedule. “You see the pictures of all those guys inside, and well, they had enough to cover it.”

There were seven men in the crew at one time, and each man took his turn cooking; they even made their own bread, historical documents showed. The second floor of the building consisted of one spacious room where each man had a bed and a foot locker.

A watch tower at the top of the building (the interior is shown in the video embedded at the top of this story) provided a 360-degree view of what was then a sparsely-populated island, subject to rescue calls when ships bound for New York harbor drifted off course or misread the location of the Barnegat Lighthouse.

“You have to imagine that there was just sand here – no road, no boardwalks, hardly any buildings,” said Amabile.

Councilman Ray Amabile and Mayor John Peterson lead a tour of the historic borough hall. (Photo: Shorebeat)

Councilman Ray Amabile and Mayor John Peterson lead a tour of the historic borough hall. (Photo: Shorebeat)

The gable-style lookout point, however, was not the only way Life Saving Service crews could detect ships in distress.

Today, passersby might notice a small white building along the boardwalk just south of the Sawmill bar and restaurant. Most recently, it housed a small radio studio that some local stations used to broadcast live from the beach. At one time, however, that building was simply a base structure that supported a much larger tower. Though the height of the tower was not readily available in the records Shorebeat located, it provided an extended level of protection for mariners and allowed for a better chance of crews finding an imperiled vessel.

Though the tower has since been taken down, the small white building remains. Like the town hall facility across the street, many of the original materials can still be found behind the more modern facade, and the construction of these structures – more than a century later – is difficult to question.

“Think of all the hurricanes this building survived,” said Peterson, the current mayor. “Even in Sandy, everything was dry and everything survived – the records, everything.”

Unique Technology Keeps the Station Alive

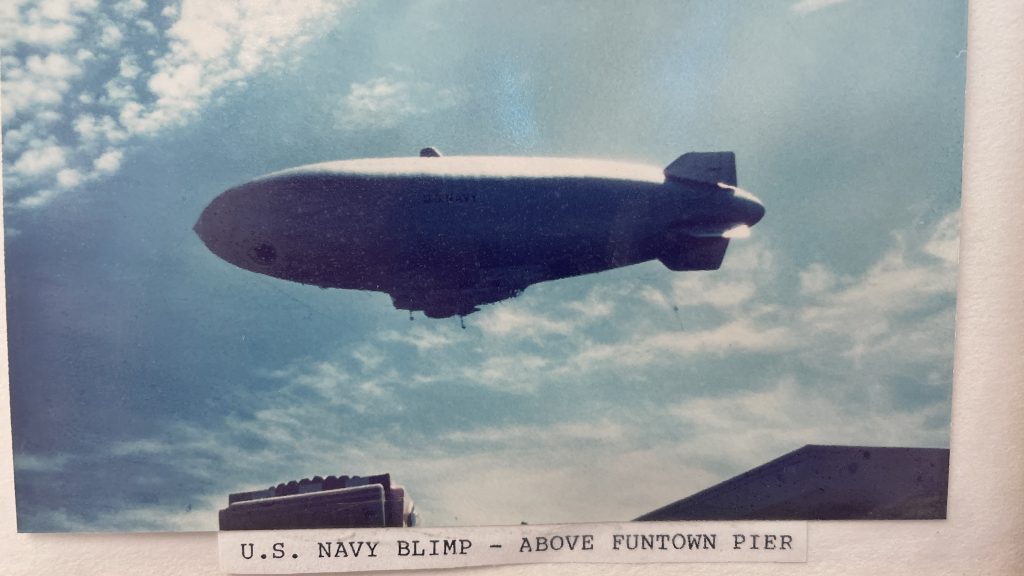

Following the second World War, technology received a resounding boost. Radar capabilities and communications methods were advancing rapidly, and even recreational boaters were using powered vessels for weekend fun. The modern Coast Guard was tasked with an increasing number of missions, and was more agile when faster, more powerful and resilient vessels could plow through breakers at inlets after being launched into the bay as opposed to directly into the surf.

One of the vehicles that was essentially invented for use during the war, however, was responsible for the old Life Saving Station to remain open in Seaside Park for nearly two more decades. With a location about halfway between Manasquan and Barnegat inlets, it was determined that the Life Saving Station should stay active – with new technology.

So-called “Duck Boats,” the name given to the DUKW amphibious combat vehicles utilized in World War II and the Korean War, were available in surplus. Without a war raging, some were converted to civilian rescue use, including at least one delivered to Seaside Park. The same bay doors that once opened for crews to haul surf boats out to the ocean were modified to allow the entrance and egress of duck boats, which would glide over the sand and enter the water to effectuate a rescue.

More than 21,000 DUKW 38-foot amphibious craft were produced by General Motors-Chevrolet between 1942 and 1945, though their subsequent short history in U.S. Coast Guard service is rarely discussed.

“The DUKWs acquired from the U.S. Army were constructed of sheet steel,” one historical document from the USCG said. “The following modifications were made by the Coast Guard: installation of an aluminum alloy cover over the driver’s area and extending aft over the forward part of the cargo space; a self-bailing cockpit in the after part of the cargo space; a walkway along each side of the cover; towing bitts and tow rail; and navigational lights. In 1948 the Coast Guard constructed additional units at the Coast Guard Yard, Curtis Bay, MD. These had aluminum bodies and incorporated the experience learned from using the Army model. ”

In Coast Guard service, the duck boats were found to be excellent in performance of flood relief efforts, however maintenance was difficult and salt water usage took its toll. The DUKWs were retired in 1968, just a few years after the Life Saving Station in Seaside Park was shuttered.

The duck boat was retired when the station was closed in 1964, and Shorebeat was unable to find records tracing its fate.

A Proud ‘Coast Guard Community’

After the McDonald’s proposal did not pass muster with residents, it was decided that the historic building should be preserved. Ideas were batted around, and in the 1990s, the decision was made to restore the building, preserve its historical components, but install enough technology to have it operate as a new municipal building, with some room for small clubs and groups to meet.

“All of the original beams and original wood is still here, even in the otherwise-renovated offices,” said Peterson.

As employees dutifully fielded phone calls from residents and worked at their computer screens in the comfort of air conditioning and friendly banter, a Shorebeat reporter could see the massive bay doors at the front of the room. The modern office was, indeed, where crews once launched vessels to save lives and stored and maintained duck boats to respond to rescue missions and flood relief operations after storms.

Though it may not be an intentional homage, the garage behind the building is still used for storing lifeguard equipment, continuing the goals of the original Life Saving Service to this day.

After Seaside Park completed its move, Coast Guard officials returned to the site and held a ceremony that allowed its ensign to fly underneath the American flag outside. It was a proud moment Amabile said he will not forget.

“We fly the Coast Guard ensign like any other Coast Guard base around the world, because we’re a Coast Guard community,” he said.

Police, Fire & Courts

Toms River Man Sentenced to Prison for Assault, Eluding, Robbery, Threats